They say when you’re born, you come into life with no instruction manual.

If we’re lucky, we inherit a good set of parents, who set us up with good habits and sound thinking.

We might pursue a religious practice, embrace an education, and learn to think for ourselves.

Others might not be so lucky. Anxious and unsure — we turn to other things to make sense of reality — drugs, alcohol, sex or easy money.

Without a set of instructions, we rely on what we think is our operating system: the ego.

And we protect it with all our might.

It is the ego, after all, that gets us into fights, creates resentments and wastes our time thinking about the past — ignoring the glories of the present. We find ourselves angry and irritable — pissed off at a coworker, cut off from a relative, mad over current events. And it is a devotion to an ego that makes us powerless to predict life’s terms or life’s turns. We end up more wrong than right, and our ego rages in response.

I came across Scott Adams accidentally, but it couldn’t have come at a better time for me.

It was around 2015 or so, and I was hot and bothered by Donald Trump.

My friends and relatives had jumped aboard the Trump train, but I resisted — and resentfully so. I had my reasons for it, no doubt. But I never question what lurked beneath those reasons. Turns out it was self-doubt — the weak armor of an insecure ego.

I found myself dreading work, and angry that nearly all my predictive powers had failed. Every day I would say, ‘Trump’s finished!’ and he only got stronger. This wasn’t like me.

But one day on Twitter, some soul I’ll never be able to thank tweeted a simple suggestion: read Scott Adams. And, in a rare moment, I decided to heed a comment on Twitter. I googled Scott’s blog. And it changed my life.

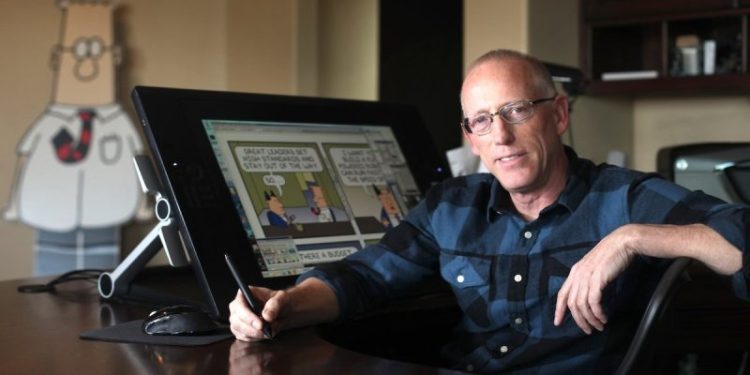

Scott was already a world-famous cartoonist, of course — the creator of ‘Dilbert.’ He had a pile of bestsellers.

Scott loved humans, but understood the nature of their pain — caused by how little they understood the reality behind the one they took as real.

But I knew little of that world. And I had no idea what I would discover when I entered the Scott Adams universe — a place where the most profound thinker ruled with a cup of coffee, a goofy grin and a deep understanding of moist robots — i.e. humans.

Scott loved humans, but understood the nature of their pain — caused by how little they understood the reality behind the one they took as real.

While some people would tell you they knew life’s secrets in order to impress upon you their brilliance — Scott was only trying to help. It’s why Dilbert was so successful. He was expressing the reality behind the reality. And we immediately got the joke.

Reality is subjective. And we see things as we think they are — not how they really are. And we foolishly make predictions based on those assumptions.

We had no answer key to life — and for many of us, that led us to making the same mistakes over and over. But Scott explained to us the conceptual reality behind the physical one — and it was the world of persuasion. He calmly explained how it operates — which in time made it possible to almost predict anything. Once you knew how persuasion worked, you could see around most corners.

This was the difference between Scott and most intellectuals trying to flex their brilliance.

They were interested in reversing reality — but Scott was merely trying to explain it.

And he did that every morning.

It was then, daily, that I listened to ‘Coffee with Scott Adams’ — certain I would glean some valuable insight into the world. And that prediction never failed. He would offer reframes of issues and ideas that would change the way I looked at things.

I remember Scott talking about the joys of being fired.

Having been fired 3 times in my life — I remember being angry and resentful after each one. Turned out, as Scott pointed out, I should have been grateful — because each firing was a step forward into a better career. My life never got worse after being fired — it only got better.

And this pretty much holds true for everyone. Being unhappy over a firing was based on a faulty assumption that the game had just ended. When, in fact, you were just entering a new level. The game started anew. And you could do anything.

It also helped that he framed getting fired — as well as getting dumped — through the same simple filter: that the relationship was not a good fit. Once you look at losing a job or the girl as ‘not a good fit,’ you have eliminated a wound on your ever-present ego. It’s not about you.

And that frees you from the bag of rocks known as bitterness.

The ego is something that we all have and few can control. Usually the ego runs our lives, often into the ground. But Scott reframed it with an analogy — and I quote it often…

Imagine a person asks you to carry an original Picasso down the block to a gallery. You oblige, and the journey is harrowing. You pack up the painting, you wait for the rain to stop, you walk carefully and timidly — step by tiny step — terrified of pedestrians and puddles. Now imagine that same person asking you to carry a potato. Sure, no problem! You throw the spud in your pocket and head out. And if you drop it, no big deal — it’s just a potato!

Then comes Scott’s kill shot on the ego: Right now, your ego is a Picasso. From now on, think of it as a potato.

And when I did that, I felt a weight lift. I worried less about slights, or embarrassments. If I was wrong, I embraced it. In fact, losing the ego enabled me to see the worth in being wrong — for it merely sharpened my own ideas. I abandoned the sunk cost fallacy and learned to leave stupid opinions behind.

Scott believed in a higher power — that there is more to the world than just the physical reality.

He put his money on a simulation — that God might actually be a programmer. He would often point to an underlying structure that guides us.

I hate that Scott is gone, because he helped me so much. He changed the way I thought, and by doing so made me a happier, better version of myself.

Scott hadn’t invented the idea — he was simply discovering things about life and shared them with you. This is why when you listened to his morning show you felt that you were on an anthropological dig, led by an incredibly brilliant archaeologist sifting through today’s news, showing us the things that we overlooked — things that point to a reality we didn’t know existed. You might call it God. Or a simulation. But it was there alright. A design and a Designer.

Adams pointed to a conceptual reality that lurks behind the physical one. And without understanding that secret knowledge, we are often disappointed and resentful.

When Scott would go to his whiteboard during his podcast, he would explain this clearly and without ego. He used his unique power for good -– showing you how to reframe things like laziness, or failure, death, or loss–in ways that bettered your existence.

He often referred to the mind’s mental shelf space. And while you cannot stop thinking bad thoughts (which depress you), you can crowd that stuff out and off the shelf with positive thoughts. Which is why he championed positive affirmations.

His treatment for laziness is quick and effective: imagine the outcome instead of the effort.

That tip combined both the affirmations and the shelf space analogy. Right now, your brain is focusing on the effort to do the dishes; when you could be thinking about how great it is that you have clean dishes in the cupboard and a spotless kitchen counter. You think a good thought, which crowds the bad one out — and the outcome is realized.

I am avoiding the real benefit of Scott Adams. Because it hurts. It’s friendship. I lost a dear friend, someone I loved. A mentor obviously, but a friend I adored.

In his podcasts, Scott offered his hand to everyone — he would be there, 7 am West Coast time, whether you showed up or not, because he knew that whoever did show up, needed a friend.

I would exercise with Scott’s morning show on, daily — for nearly a decade. I would be pumping away on the Peloton, my ears fixated on Scott’s observations — pausing every now and then to send myself a note about something amazing that Scott just said.

When my life changed — having a baby — I ended up not being able to listen to Scott live — so I looked forward to the comfort of a podcast banked for later.

I am avoiding the real benefit of Scott Adams. Because it hurts. It’s friendship. I lost a dear friend, someone I loved. A mentor obviously, but a friend I adored.

It was a good feeling to remember that, ‘Oh yeah, I have a Scott Adams I didn’t get to!’ It might be Scott’s greatest accomplishment — creating a community of gentle, intelligent beings who met every morning to share in a sip of a beverage of their choice. Those who didn’t get it… well, too bad.

There are those who remain critical of Scott — but I attribute that to their ignorance. Not ignorance in general, but specific to Scott. They just had no idea what they were dealing with, when they disparaged him. It’s like rejecting a gold bar because it’s too heavy.

Fact is, the more you got to know him, the more valuable he became.

He was the exception to his own frame known as ‘The Basket Case Theory’ — which stipulated that once you got to know someone you admired or envied — you’d find out they’re just as messed up as you.

It was an excellent frame for people with anxiety or shyness. You might think that the unfamiliar people are judging you in that hip restaurant — but really, they’re too busy judging themselves. They have their own problems and trust me — you wouldn’t want them.

Scott once was posed the question: would you trade your life with anyone? It’s a good question for those of us who envy the rich and famous.

But Scott said that you have no idea what the problems are of other people. The rich playboy may have syphilis; the popular actor may be riddled with alimony and addictions; the accomplished artist is almost always a nervous, palpable wreck. It was a simple reframe that helped dispense with jealousy.

But Scott’s own life subverted this frame — sure, he had his own problems; but the more you got to know him — that fuller picture made him only that much more endearing.

At a certain point in his life, Scott decided to devote himself to service, and he brought that service up to his dying breath. Instead of extinguishing the flame with assisted suicide months ago — once he felt the love swirling around him – he decided to stick around for our sake.

He wouldn’t leave us, not yet anyway.

He even reframed his death: that one’s death is a relief for the dying, for their problems have gone. It is we who are in pain, not him.

And it’s our selfish pain — that he decided to be there for!

I hate that he is gone, because he helped me so much. He changed the way I thought, and by doing so made me a happier, better version of myself.

I fear I will lose that gift now — with him gone, and I told him so a few months ago.

To which he said, ‘No, you got it now.’